We use a carbon tax or an emission trading scheme to stimulate investment in clean technology. The logic of this idea is based on several steps: we charge people for emitting CO2 and as a result some will find ways not to emit. Some of the ways people find not to emit will involve developing and implementing clean technology.

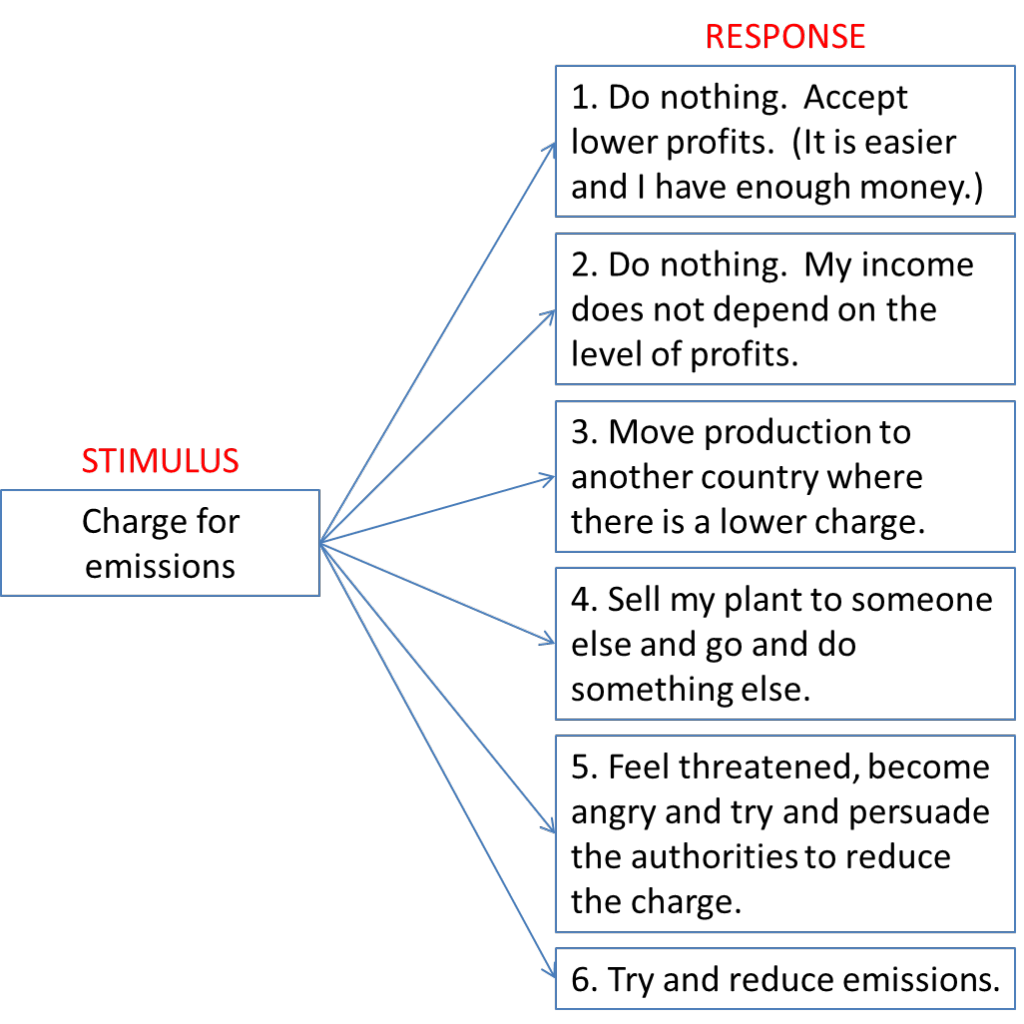

Let’s think of the other things people might do when faced with a charge for emissions. They might just carry on, because they have plenty of money and it is easier to do nothing or because their own income does not depend on profits. They might move their production to another country where there is not a charge or a lesser charge for emissions. They might become cross and try to persuade the authorities to reduce the charge for emissions. They might sell their business and go and do something else.

We can draw a picture of this. There is a stimulus (charge for emissions) and several possible responses.

These are six different responses which I came up after only a few minutes thinking. With more thinking and research we can surely uncover many more responses to the stimulus.

Some of these responses have no effect on emissions, some do, and in some cases we cannot tell. For example, if I sell the plant (at a depressed price because of the emissions charge) to someone else, then the buyer, having bought at a depressed price, might be generating nice returns even with the emissions charge and so he moves into the first response category. If the buyer is a creative and eager type, he might take up the challenge which the seller baulked at, and try and reduce emissions.

We can consider the conditions which the influence the response. There are conditions of circumstance – external circumstances which constrain the decision-makers; and of belief and temperament – internal characteristics personal to the decision-makers. Here are some suggestions:

The point made here is that for a company to try and reduce emissions in response to the stimulus of a high carbon price, you want certain circumstances to prevail and you want the decision-makers to have certain beliefs and temperament.

In what percentage of companies do you have the right combination of circumstances and beliefs / temperaments?

Do we know?

We have some idea of the circumstances surrounding companies – hence the whole discussion of the “leakage list” which in a way makes an attempt at determining the probability of a company shifting production abroad. But this does not give the whole picture.

I don’t think that the temperament and beliefs of decision-makers have been examined.

Is there anything we can do to guide or nudge the response to the stimulus towards (6) and away from the others, especially (5)?

We should discover this, because efforts to increase the propensity of decision makers to go the way of (6) might be more effective and politically acceptable than simply increasing the charge for emissions which is the only option that the EU ETS gives us.